Advice for Newly Diagnosed Cancer Survivors

And the People Who Love Them: From Those Who Learned It the Hard Way

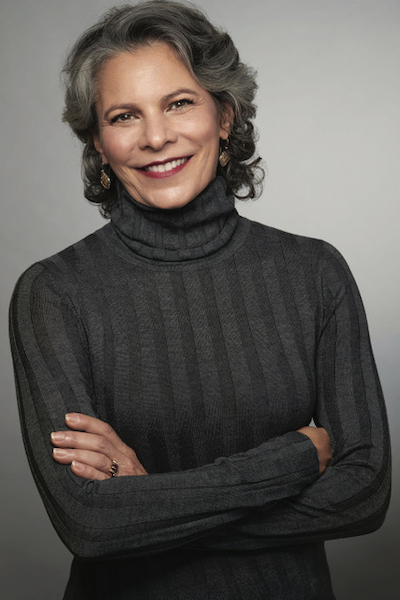

By Cynthia Hayes

This article was adapted from The Big Ordeal: Understanding and Managing the Psychological Turmoil of Cancer.

This was written to help you learn from the wisdom of those who have gone before you, fellow travelers on a journey none of us wishes to take. Based on interviews with over one hundred cancer survivors, including those newly diagnosed, in treatment, recovering, or facing their final days, it presents real-life situations and real emotions, as well as advice from real cancer survivors.*

When You Hear the Words “You Have Cancer”

Shock, stress, tears, anxiety, denial, or even relief – emotions erupt at the time of diagnosis with surprising strength and complexity, reflecting who we are, how threatened we feel, and our diverse ways of coping. Regardless of how we internalize and express the emotion, though, most of us are left with a powerful recollection of the moment we understood we had cancer that suggests we experienced some degree of stress. Fueled by a cascade of hormones released in the moment of crisis, we can easily recall the visceral reaction we had to the news, whether it was fifteen minutes ago or ancient history. For many, the emotions evoked in that moment dissolve and shift as we move into the next phase, but for others, the response to diagnosis sets the course for the rest of the ordeal.

“So many people don’t want to talk about it, but when you allow people in to share it with you, it makes it less scary.

As Carol said, “Each of us has to find our own best way to deal with cancer.” But survivors who have been there shared some common thoughts on how to get through those difficult first hours and days: “It really sucks,” said Susie, “but you have to get beyond that.” Or, as Deborah put it, “Experience what you are feeling. It is scary. Acknowledge that, and then move on.” Anne agreed: “It’s helpful to remember that most of us live. It isn’t a death sentence, and it’s not a judgment or a punishment. It’s just a disease.”

How do you move beyond the shock? Some take an aggressive stance, as Lulu did. “Obviously you are going to cry and be upset and be mad, but at some point, you need to stop, you need to concentrate your mind on getting ready to fight, with victory as your goal,” she said.

Others prefer a more measured approach. Mark said, “You can’t swallow the whole thing in one bite. Take baby steps; worry about just one thing at a time.”

But no matter what, it seems to help to recognize that there will be good days and bad days ahead. As Fatima said, “It’s going to be a roller coaster ride, but keep your faith up and do what you need to do.” And many survivors counsel, as Charlotte did, “You are stronger than you know you are. It’s not easy, but it’s not terrible either.” Still, no one is expecting you to be stoic about it. Nancy H. said, “You don’t have to be a superwoman about it. It’s normal to be scared, so go with what you need, what feels right to you.”

Often, what feels right is relying on others for support. “Don’t be afraid to share it,” said Deborah. “So many people don’t want to talk about it, but when you allow people in to share it with you, it makes it less scary.” Nina agreed: “Surround yourself with supportive people. You don’t need people who aren’t helpful. You need to stay positive and not go to the dark side.”

Or, as Robin A. said, “Find some support, whether it’s family, close friends, or an online support community of others who have been there. It really helps.”

And with the support of others, seek out the best possible care. “Get the best medical care that you can,” said Diane. “You have to do a little digging, a little homework,” Jill R. agreed. “Talk to friends and doctors and people who have been there to gather as much information as needed,” she said. “Information is powerful.”

“But don’t scare yourself,” cautioned Loretta. “Every cancer is different.”

Good Intentions, Bad Results: How Not to Support a Loved One Facing Cancer

When people hear devastating news about a loved one or a friend, they, too, can feel shocked and blindsided. They want to offer support, say something comforting, and do the right thing, but may not know what to say or how to show they care. Without thinking, they repeat statements they have heard or said before:

- “Everything’s going to be all right.”

- “You’re strong. You’ll get through this.”

- “Let’s not panic until we’re sure we have to.”

While meant to be encouraging, comments such as these can negate the very real fear a newly diagnosed person is feeling, landing more like slaps in the face than the show of support they were meant to be. Survivors often just want someone to recognize that they are afraid – that cancer is scary, and their feelings of terror are valid.

Monica had lots of friends and family support when she got her diagnosis, but that didn’t mean everything she heard was supportive. “The last thing I wanted was someone telling me, ‘Of course you are going to get better, it’s all going to be okay’ – it’s just so insensitive and denies the mortality issue staring me right in the face,” she said. “Even the offhand comment about the irony of me getting cancer when I was the one who always took care of myself wasn’t really helpful. You have no control over who gets cancer or who is going to die from it.”

Rachel recounts feeling disconnected from her husband at the time of her melanoma diagnosis. “He desperately wanted to be the one who was there for me but was missing the point all the time. I was scared, and his telling me not to worry wasn’t going to make that fear go away.”

Many survivors want friends and family simply to acknowledge the dreadfulness of the diagnosis. “Just say ‘Cancer sucks; I’m sorry,’” said Jeremy, a forty-six-year-old First Sergeant recently retired from the US Air Force with life-threatening cancer of the appendix. “One guy said to me, ‘Well, we all gotta go sometime.’ It was so insensitive – as if he had already given up on my life.”

“It’s helpful to remember that most of us live. It isn’t a death sentence, and it’s not a judgment or a punishment. It’s just a disease.”

Often, listening is as important as speaking. “Cancer is so huge. You can’t assume anything about an individual’s experience or reaction unless you ask. But you have to be prepared to listen,” suggested Elyse, battling a rare type of lymphoma. “Just show up and be present. Don’t try to fix things or pity them. Just be with them.”

Where to Find Support

It’s hard for people who haven’t been through it themselves to understand the fear associated with a cancer diagnosis, which is why so many survivors find solace in online or in-person peer support, both through individual mentoring and in groups. Whether broad-based or specific to a particular kind of cancer, peer support allows survivors to share real and raw emotions and to find support for getting through the physical and psychological trauma of cancer.

“I joined the online support group Bladder Cancer Cafe,” said Brian, “and stayed on for a long time after the initial stages of the disease.

I found it incredibly reassuring to be in touch with others going through the same thing and felt very bonded to the people in the group; they offered support, advice, research insights. There’s a lot of help out there, even if you can’t find what you need from family and friends.”

For those looking for support, the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Survivors Network is a great place to start. And there are online support groups specific to most types of cancers. Many hospitals and cancer centers offer in-person support as well. One-on-one counseling, peer-to-peer programs, group discussions, and active therapy, such as writing or exercise programs, are increasingly available for cancer survivors. If you or a family member needs support, ask your doctor for local suggestions, or check out our Cancer Survivors Guide.

When Cynthia is not on the tennis court or writing, she mentors people going through gynecologic cancer as part of the Woman to Woman program at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, and is a BOLD Buddy peer mentor to people receiving care at the Montefiore Einstein Center for Cancer Care in the Bronx. Cynthia also serves on the board of Moving For Life, a dance exercise program to support cancer recovery, and Global Focus on Cancer, which provides education and support for survivors in developing countries.

You can find Cynthia on Facebook and Instagram at @Cancer.TheBigOrdeal and Twitter @TheBigOrdeal and at TheBigOrdeal.com.

This article was adapted from Cynthia’s book The Big Ordeal: Understanding and Managing the Psychological Turmoil of Cancer.