The Man I Love Has Cancer

by Yvonne Watterson

The man I love has cancer. And, after months of deliberation, of decisions made and decisions overturned, he has begun treatment. Radiation treatment. Every single day. For forty more days.

With my own cancer treatment in the rearview mirror, I thought I would just know how to help him, how and when to find the best and kindest words to lift him up, to quell the fear, to be “there” for him. Then I remind myself that undergoing cancer treatment is a private act, with stretches of time spent in a surreal and solitary confinement. Along the way, I know I can point out some of the landmarks – detection, diagnosis, treatment, shame, depression, fatigue, fear of recurrence – but I know of no shortcuts. I know he is a stranger in a strange land.

Even if I could hold Scott’s hand during radiation, while he lies perfectly still on a treatment table, he is still alone. Supine, his mind is ablaze with haphazard thoughts, ranging from the pedestrian to the philosophical. What if he sneezes? What if he dies before he sees his daughter grow up? Why in the hell did he get cancer in the first place because dammit he feels just fine? What if this was a mistake?

He will try to ignore the strategically placed signs above him – “Tell cancer it has two months to live.” “Hang in There.” “You never know how strong you can be until you have to be.” “Together We Can Beat This.” Skeptical and uninspired, the man I love is an unwilling conscript in this battle.

Healthy, handsome, fit, Scott wasn’t supposed to get cancer. It was supposed to happen to someone else, someone with a family history, someone who didn’t go for routine physicals, someone who didn’t feel well – someone “destined” for it. Not him. It wasn’t supposed to happen to me either. I remember once upon a time when I thought breast cancer was the thing that was supposed to happen to other people, to celebrities who grace the pages of magazines, to women who didn’t show up for their mammograms, to women with a family history. It was not supposed to happen to me.

In a “you go first” moment, I laid my cancer card on the table. Buoyed by this, he shared that he had been diagnosed with prostate cancer four months prior.

Denial works for us, doesn’t it? It’s why we travel on airplanes. We know they might crash – but never when we are on board.

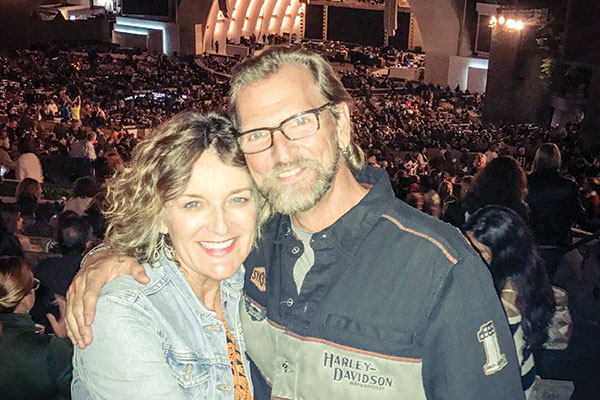

The first night we met, he told me about the cancer. Over beers and banter, we sized each other up and overshared, checking off boxes our middle-aged online personas had created on a dating site. A musician, he told me he loved Bob Dylan and golf and taking to the road on his Harley Davidson. Regaling me with the stuff of good first impressions, he glossed over a comment about illness and aging. A dog with a bone, I pressed for details, and in a “you go first” moment, I laid my cancer card on the table. Buoyed by this, he shared that he had been diagnosed with prostate cancer four months prior. He was still considering his options and assessing the potential damage of various treatments. I had just met him, and already I knew he was bruised and alone and drowning in fear of what was to come. He was in the waiting place.

Just as I had known nothing about breast cancer until it happened to me, I knew nothing about prostate cancer or its treatment. As evolved as our society is, we still refuse to entertain certain diseases, disorders, addictions, and ailments in polite conversation.

Unlike the common cold, its symptoms unapologetically made public with sniffles, sneezes, and loudly blown noses, prostate cancer symptoms often go unnoticed, revealed only after a routine screening. Such was the case with Scott. When his first digital rectal exam and PSA test indicated he should keep an eye on his prostate, there was no sense of urgency. I imagine he told himself that most prostate cancers found by screening are small and insignificant. Slow-growing, they may never cause any problems. In his research, I’m sure he also found that for some men, false-positive results lead to biopsies which show that there is no cancer at all. Others will endure biopsies that find cancer, but the cancer might not grow quickly enough to be life threatening. Sometimes, these cancers are treated with radiation or surgery, accompanied by side effects that nobody wants to talk about – infection, incontinence, impotence – leaving men like Scott to ponder silently their mortality and their sexuality as they contemplate their next move.

Scott doesn’t believe it’s happening to him, which explains why some people closest to him don’t even know. Cancer pushes a lot of buttons. It changes us, forcing us at the most inconvenient of times to confront our mortality. It can transform us into great pretenders, and so we distance ourselves from those who love us most – out of fear and self-preservation, or indignation and anger about the fact that our number simply came up, or maybe out of denial and shame and all the other words found in the recommended self-help books that we cannot bring ourselves to read. Sometimes we don’t know what to do or say, and we might even turn our backs on the people we used to be.

And then, in a rare moment of clarity, we realize that’s no way to live, that something good is coming, and that love never fails.

Yvonne Watterson is a breast cancer survivor living in Phoenix, AZ.

This article was published in Coping® with Cancer magazine, November/December 2017.