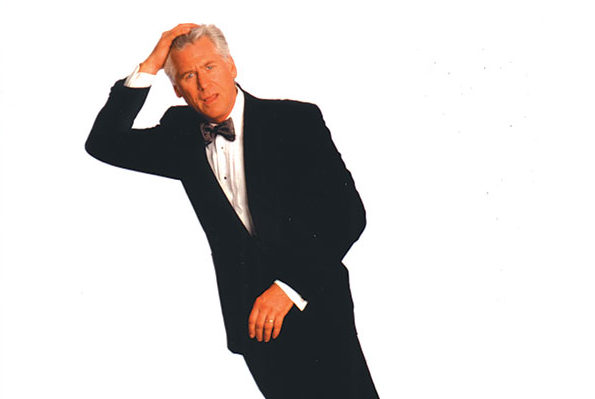

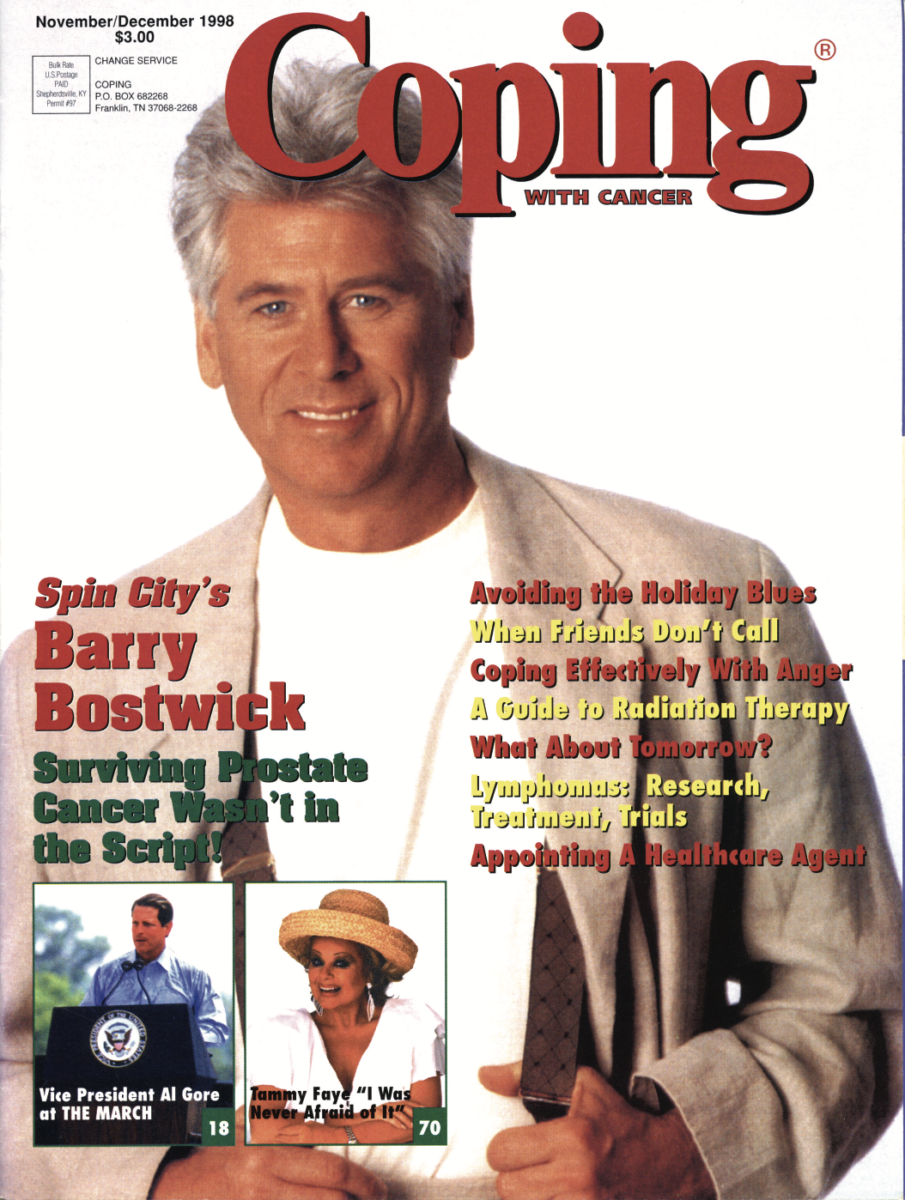

Spin City’s Barry Bostwick

Surviving Prostate Cancer Wasn’t in the Script!

an exclusive interview with Cindy Phiffer

You may recognize Barry Bostwick as ABC TV’s Spin City Mayor Randall Winston, Broadway’s original Danny Zuko in Grease, Brad Majors in The Rocky Horror Picture Show, Pirate King in the 1981 Joseph Papp production of The Pirates of Penzanze, or Lt. “Lady” Aster in War and Remembrance.

Of all the roles he’s played, none has required more from him than his current role as prostate cancer survivor. In May 1997, after a successful debut year of Spin City, Bostwick was diagnosed with prostate cancer using a PSA (Prostate-Specific Antigen) test prompted by a bout of prostatitis. The 53-year-old immediately went to work studying for the part by gathering information on the treatments available including radiation, hormones, seed implants, cryogenics, watchful waiting and surgery.

The decision, a tough one for anybody, was especially critical for the veteran actor and family man. He and his 36-year-old wife Sherri Ellen had already been through a lot in their four years together. “We’d had a marriage, two children … Brian was two-and-a-half and Chelsea was less than a year old … I’d gotten this new job so we’d moved from California to New York state, and I was advised by my doctor that the wisest thing, given my age and given the size of the tumor, would be having a radical prostatectomy done as swiftly as possible. From what they could gather, it was still contained in the prostate and it hadn’t metastasized.”

This decision, eventually made together as a couple, was made so that Bostwick would “be around for the long haul” with his young children. It also seemed to be the logical choice for Bostwick the actor.

“Spin City was on hiatus,” he recalls. “Because it takes a lot of energy and a lot of focus and a lot of good humor, I didn’t want to have to come back to the show with ‘the big question mark.’ There’s always going to be a question mark because of the possibilities of it returning, but I didn’t want to start my work year at the end of July without having done something positive to get at the source of the cancer.”

Bostwick’s medical team assured him that the operation would be as nerve-sparing as possible. A radical prostatectomy would remove the prostate, a muscular gland situated about the base of the male urethra which secretes an alkaline viscid fluid, a major constituent of the ejaculatory fluid.

Navigating the entertainment industry continues to go smoothly for this versatile actor, but the channels of personal intimacy have been more difficult to maneuver.

“I thought, I can deal with incontinence. You can just wear diapers the rest of your life,” Bostwick explains candidly in a smooth, even voice that would make a believer out of anyone. “I thought, I can deal with impotence. There are ways in which you can get an erection. My doctor said that probably within a year or a year-and-a-half, I would maybe get back 80 percent of my own pre-op sexual functioning. He’s a pretty conservative guy, so I thought, It’s better than none.“

Bostwick had the surgery on June 24, and returned to the ABC sound stage when the lights came back up on Spin City six weeks later. By this time, his employers and co-workers knew about his prognosis, although he had kept the news quiet until after the operation.

“We wanted to get the pathology back to see where I stood before we let people in on it,” he says. Although attitudes in the workplace are much different than they were years ago, he wanted to know what his prognosis was so that he knew what he was dealing with. “Once the pathology was done on my prostate, my Gleason score was lower than what it was when they took the biopsy. That was very promising, not only for me, but for people who are looking at me as an employee.”

Apparently, Bostwick’s strategy worked. At a recent fundraising event, he ran into the president of ABC. “Ten years ago it would be very difficult for somebody like myself to talk to his boss’s boss because you were afraid that they would recast your part or kill your character off,” says Bostwick, “but he was more concerned about it from a man-to-man standpoint than as an employer.

“The first thing out of his mouth was, ‘How are you feeling?’ I said, Tm feeling great!’ He said, ‘You’re looking great,’ and that was the thrust of our conversation rather than tiptoeing around it or not even bringing it up, which probably would have happened a while back.”

Navigating the entertainment industry continues to go smoothly for this versatile actor, but the channels of personal intimacy have been more difficult to maneuver.

“The emotions of having had a prostatectomy have caught up with me post-op in dealing with the residual effects of incontinence, impotence, all the things we were told about,” he admits. “Dealing with some of those things is certainly more difficult than the thought of dealing with them.”

Along with experiencing a sense of loss as a result of the surgery, Bostwick went into a slight depression during the first year. “The stress of the recovery got to me and I went on a low-dose anti-depressant,” he continues. “The incontinence was dealt with pretty much so in the first three or four months and now it’s just occasional. At first, you think it’s gonna cure itself and you’re gonna be able to forget about it, but when it happens occasionally, you go, I’m gonna have to live with this stress-related leaking the rest of my life.’ It’s nothing dramatic; it just wears on you in a very subterranean way.”

As he continues to tell his dramatic story, Bostwick’s voice picks up again, playing up the comic aspects. “Then you realize, I guess this is going to be an on-going problem. I’m just gonna have to buy more underwear.”

“The impotence has been a problem since the beginning,” according to Bostwick, “and it continues to be a problem. I went through all the stages of trying to get it working again with the various ways.” He tried everything from a urethral suppository to the pump to different sorts of rubber bands. None of these worked for him.

“I finally started using the shots,” he says, refusing to give up on such an important part of his life. “They are amazingly accurate, once I found the right dosage, and they’re relatively painless.” But the couple had to face a loss of spontaneity.

Refusing to give in to a tragic point of view, Bostwick pulls his sense of humor back out of his bag of tricks. “The problem with all of this is that the erection is not really related to the sexual act. I find that very disconcerting because usually part of the excitement of the act of intimacy is being excited by your partner and now you’re getting excited by a drug. Then, when the sexual intimacy is over with, you ‘re still excited. It’s difficult to deal with because you’re so used to having a certain rhythm to your sexual encounter. Now, there’s no immediate relaxation or a sense of well-being because you still have an erection for an hour and it becomes like, ‘Get out of here. We’re done now. That part of the day is over with.’

People like me can go out and grab the spotlight three or four times a year and get applause and recognition for our cause. But it’s the volunteers that are in the trenches day after day who are the real heroes. I don’t have that kind of personality. I’m not that selfless.

“It requires a sense of communication and understanding between the couple that’s very mature,” he says, then speaks about his wife specifically. “I’m blessed with a wife who is in it for the long-run. She’s not selfish in any way in terms of her own needs, and she’s been there for me. At the same time, she has been dealing with her own anxiety about it in a very quiet way.”

Bostwick pauses for an uncharacteristically heavy sigh, then looks again to the bright side. “But I think like any cancer survivor’s family, there’s probably an increased sense of intimacy between the couple because of what they’ve had to deal with in terms of what the cancer has brought into their lives and the decisions that they’ve had to make.”

Because of his incurable optimism, the encouragement of a loving family, and a strong will, Bostwick refuses to take his prostatectomy recovery lying down. With the increased availability of Viagra earlier this year, Bostwick became one of its earliest users, starting with a very low dosage and working his way up to a level that works for him. His relief at going from injections to pills is palpable.

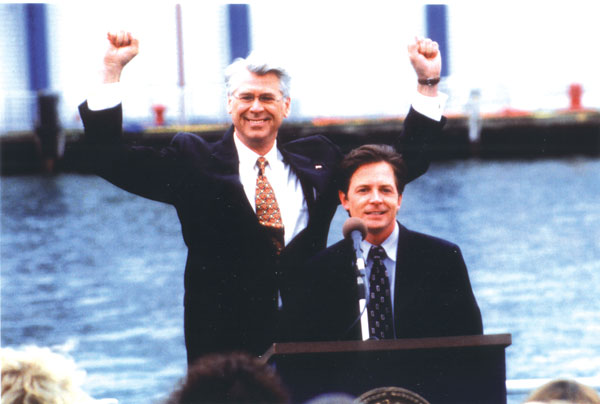

Comfortable in the limelight, Bostwick uses it to draw attention to the need for continued funding for research. “The upshot of this whole cancer thing is that it has gotten me involved with a lot of people who are passionate and dedicated to the cure of cancer. It has given me a place to use that reservoir of service we have in us.

“People like me can go out and grab the spotlight three or four times a year and get applause and recognition for our cause. But it’s the volunteers that are in the trenches day after day who are the real heroes. I don’t have that kind of personality. I’m not that selfless.”

Barry Bostwick may not be selfless. And he may not always be the hero. But in the fight against prostate cancer, he’s a convincing leading man.

This article was published in Coping® with Cancer magazine, September/October 1998.